At the edge of the world, on the island of R’evava in the Arctic Ocean, a blizzard rages outside as five people gathered in a small weather station pass the time telling each other stories while they wait for a break in the storm . . .

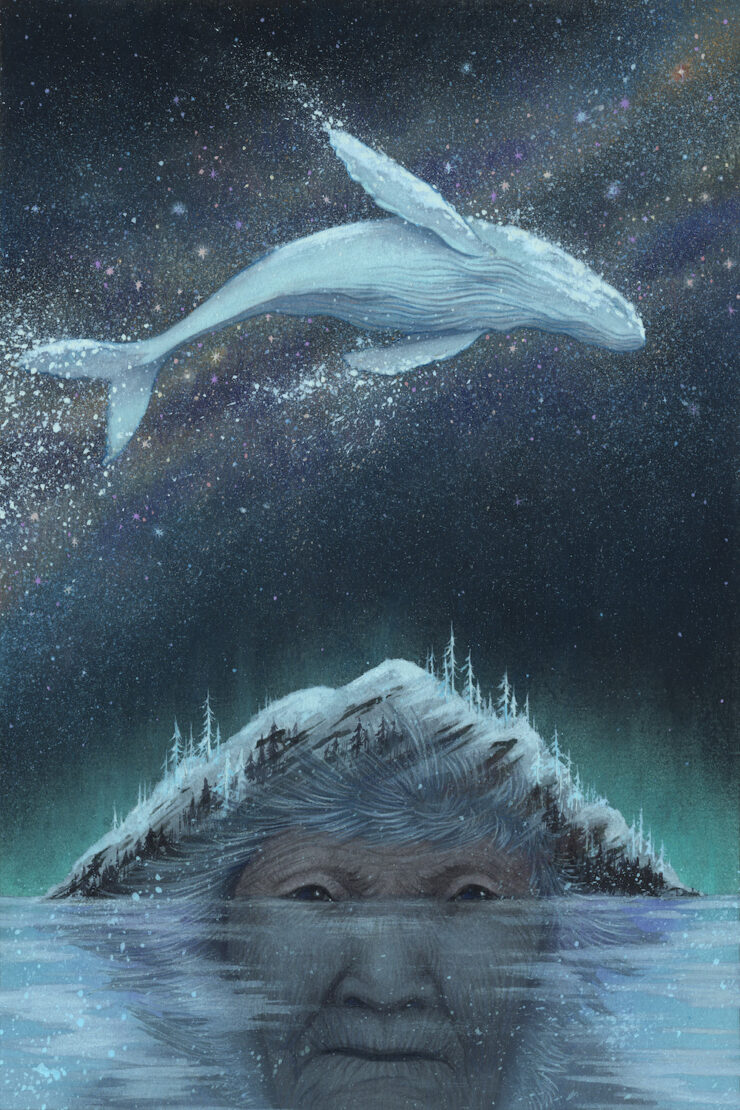

Umilyk: Fable of the Mother of White Whales

“They say the blizzard on R’evava is the wrath of the snow whale. It beats its tail against the infinite surface of the Milky Way and shakes loose small snowflakes that cover the island,” said Umilyk.

He said this to break the silence and to somehow counter the wind howling beyond the fragile walls of the weather station. The silence Umilyk preferred was the silence of solitude. Here, in the company of travelers waiting out the storm, the silence disturbed him.

“In all of the Soviet Union snow is an atmospheric phenomenon, and only in Chukotka is it a cosmic one,” added Borisov.

“Not even in the whole of Chukotka, but on R’evava. For what is Chukotka but a word? An administrative unit, a geometric shape marked on a map with a ruler. To listen to those cartographers, they think even Magadan will pass for Chukotka.”

“Those are some rabid cartographers. Don’t listen to them. Listen to me. Better yet, tell us what makes your R’evava so special? Why is snow an aggregate state of water everywhere else, but it turns into shards of eternity on this island?” asked Borisov.

Before answering, Umilyk looked over the room with a certain degree of tenderness. Everything here was right and calibrated, so it was no shame to entertain guests.

Even a group of guests as peculiar as this.

A young woman with light, almost white hair and dead eyes, eyes which looked the way they do when the last of the tears have run out. Even through several layers of clothing, Umilyk could clearly see that the woman was with child. The habits of pregnant women change: they must now protect more than just themselves. And even if their taste for life dissipates along with those last tears, the maternal instinct remains.

A tall bald man in glasses with thick lenses looked like a professor, and enunciated his Russian words with an exaggerated care. Umilyk already knew that this man was from Poland and that he was no professor, but some sort of a musician.

The second man, with a rough pockmarked face, a constant smirk, and unruly hair, was a reporter from Moscow who was in such a hurry to return to the mainland that he’d traveled from Kytoorken to R’evava, only to find a blizzard instead of the scheduled helicopter.

But the presence that seemed strangest to Umilyk was that of the old woman. She crouched near the entrance in such a manner that it seemed she was ready to get up and leave as soon as the storm would pass. Her name was Navetyn and she’d lived for a hundred, if not two hundred, winters, or so those who were born and grew up on R’evava had told Umilyk. Umilyk himself was a “lifer”—a slang word from the lexicon of Soviet officials who occasionally wandered as far as R’evava. He’d spent nearly thirty years here. When Umilyk had first arrived, Navetyn was already old, like the island itself.

Her yaranga stood apart from everyone else’s dwellings. On occasion, Umilyk thought that when Navetyn died it would be a while before anyone found out. But she was in no hurry to die; on the contrary, she impressed with her sharp mind and a clear sense of time. She always knew in advance about a successful hunt, and when the whaleboats returned filled with fat prey, Navetyn waited for them at the shore with her pekul knife. She was as dexterous as the best workers in the cutting brigade and her presence was always welcome.

Which made it even more surprising that Navetyn had turned up at the village at such an inopportune time, an hour before the first November blizzard.

A village was an overstatement. There were no administrative buildings or even a culture club on all of R’evava. The weather station was the center of life, and that’s where the group had gathered, waiting for flying weather.

Umilyk sighed. Providing visitors with local flavor was not a task mentioned in the job description, but it was no less important than keeping an accurate meteorological log. He launched into a story.

“Once upon a time, there lived other tribes in the north alongside the Luoravetlan peoples: walrus people, bearded seal people, and even whale people. Men of these tribes married human women and so propagated their intelligent kind. One time, a great whale, the mother of white whales, arrived in these lands, and she took a Luoravetlan hunter as her husband. All the great whale wanted was to teach her first husband a lesson, for he was the headstrong snow whale that swims the Milky Way and whose song people hear on the border between reality and dreams.

“But the children the great whale had with her Luoravetlan hunter were as precious to her as the white whale’s. When the children grew up they prayed: Mother, we can’t swim with you into the ocean but there’s no room for us here. All the best land is occupied by other people, what should we do? The great whale listened to those pleas, sighed, and turned herself into an island so that her children would have a land of their own. This island was named R’evava. She left only one command to her children, and those words are passed from generation to generation: white whales are brothers, and one doesn’t kill their brother. They say that the great whale herself sometimes appears to the island residents in human form, to see how her children are faring.

“This is why the great snow whale always singles out R’evava, and why he brings the blizzard. He comes in search of his wife, who left him for a human man and his children.”

Borisov: The Tale of a Whaler

The blizzard howled outside and beat against walls and tiny windows, tapping on the roof like a northern giant probing for a weak spot in a dilapidated dwelling.

Borisov could see right through the caretaker. He noticed the moment when the duty of entertaining uninvited guests became something more intimate and important to him. It briefly seemed to Borisov that he’d glimpsed the huge eye of the snow whale through the tiny window of the weather station and the eye stared, unblinking, directly at him.

He recalled how much he was looking forward to this trip: a special feeling somewhere below the solar plexus. It was similar to an attraction to a woman but icier, a chill spreading through the blood and tingling fingertips with tiny needles. In this manner, thought Borisov, are born the letters that he would later build into words. He definitely needed a typewriter. An Olympia, the object of special pride and secret devotion, awaited Borisov in Moscow. He hated writing longhand as his handwriting was terrible, the beauty of ideas and clarity of thought becoming lost in his chicken scratch. But it would’ve been ridiculous to drag the Olympia north. Borisov imagined himself with the Olympia on a whaler motorboat and grinned, then grew gloomy. He was used to tracing his line of thought like a fisherman, who carefully pulls his line so as not to frighten his prey. Before the fish surfaces, the fisherman already knows by its weight and manner whether he’s about to see a catfish, a pike, or even a sturgeon.

Borisov knew which story had made him gloomy.

There was no excitement left, no special feeling anticipating his homecoming. His desire to come home was businesslike, casual, like the wish to sleep in one’s own bed after a long flight. This feeling was also reminiscent of a relationship with a woman: the romance was at an end, the attraction was over, everything there was to know about her had already been discovered and understood, and exactly as much of himself shared as he was willing to, and no more. Borisov knew he would never return to Chukotka and that made him a little sad. But it was the memory of Ettyn that hung over him like a dark cloud.

“This is all very beautiful,” said Borisov, “until it results in someone’s death.”

Out of the corner of his eye he noticed the girl wrapped in the dawn shawl shudder. She couldn’t seem to get warm, despite the hot rooms of the weather station and strong hot tea proffered by the caretaker. The Polish man didn’t look at him; he kept fiddling with his miniature vargan mouth harp. The old woman in the corner stared simultaneously at Borisov and deep into her internal abyss. Umilyk raised his eyebrows politely.

“There used to be a hunter in Kytoorken. He was very young, still a boy, but tall, very tall for Chukotka, if the honored Umilyk will forgive me.”

Umilyk shrugged as if to say, what’s there to forgive? It is true that I’m short of stature.

“The boy was named Ettyn and he was a whaler.”

Borisov recalled how difficult it had been to convince the foreman to take him along on a whale hunt. Ettyn had helped him, and he’d done so selflessly, merely for the delight of communicating with the person who’d come all the way from Moscow. Ettyn had learned the word “jovial” from Borisov and had liked it so much that he’d stuck it into every other phrase. A cargo cult, Borisov had thought contemptuously then. Now he was ashamed of his contempt.

“When the harpoon hits the whale, the tip opens. The whale dives to the bottom but the deed is done, a float called a pikh-pikh follows the harpoon into the water. And the more harpoons strike the whale, the more floats there are, which makes it more difficult for the whale to dive. That whale fought like mad, he ripped the first two harpoons out and the sea became stained with whale blood, but the hunters were inexorable. Each of them, with perhaps the exception of Ettyn, had dealt with dozens or even hundreds of whales in their lifetimes. They couldn’t be surprised by the survival instinct of a single underwater beast.”

Borisov’s cadence was measured, unhurried. When he seemed to be losing his train of thought, his imagination pictured the Olympia on a huge, totally empty desk. Under the glass-covered tabletop there were scraps and clippings of Borisov’s life: ticket stubs, newspaper clippings, napkins, and even one Aldan computer punch card. For as long as he could remember, whenever he’d position his fingers at the keys, the words would reemerge. As if they’d been stored in the fingertips and the typewriter keyboard was the means of extracting them and giving them form.

At the moment, that form was the whale.

“It was impossible to see the whale itself in all that blood and roiling. It was clear only that this was a lygirgev.” Here Borisov gave in to the temptation to use a fancy word. He tasted it as he looked at the faces of his listeners and imagined a different set of faces: sophisticated and well-fed Muscovites.

“A bowhead whale,” Umilyk explained to the woman and the Polish man.

“The Ettyn boy’s harpoon was the last to strike the whale. Next came the carbines.”

Borisov had read about how the Soviet whalers went mad. The letters of the man who wrote about this weren’t living and convincing, and his statistics didn’t give form to feeling: Borisov had read but hadn’t understood. He understood on the day when he watched an enormous and clearly intelligent creature fight for its life. It was like deicide: a seditious thought Borisov hid away, for it was only appropriate to express in secret drafts.

One could only imagine the picture of industrial slaughter, and it was an intellectual effort akin to re-creating a seascape painting from a child’s pencil sketch. Borisov winced and mentally crossed out this comparison. It was tinged with the sort of condescension for the indigenous people that Borisov was hoping to avoid. But it seemed that sickness didn’t ask for permission before entering his mind.

Borisov’s own eyewitness account of the slaughter as a means of folk harvest was sloppily recorded in his notebook so he could bring it to life with the help of his Olympia later.

“When the boats towed the carcass to the island and the tractor dragged it ashore, it became apparent that the whale was enormous, and that it was white. You know, when people mention the white whale, one imagines a snow-white color like in our comrade’s tale. Of course the whale was not literally white, but it was apparent to everyone from the first glance that this whale was special. This was also apparent to Ettyn. Do you understand what happened? It’s a very simple story. A boy goes on his first whale hunt and the hunt is successful; the boy throws a harpoon and the harpoon finds its target. The whale is caught. And then it becomes clear that, according to Grandma’s tales, this is a special whale. A forbidden whale. That its death brings misfortune to the entire clan. And instead of the joy of a successful initiation, the boy experiences some completely different feelings.”

“What happened to him?” the young woman asked, alarmed.

Borisov shrugged.

“Several days later, alone and unarmed, he undertook the task of driving off a bear and her cubs that had come close to a store. It was a foolish and terrible death. They shot the bear, of course. Even the hunting inspector recognized the shooting as justified—which is quite a rarity, by the way. It’s usually punishable by a fine to the tune of several thousand rubles. You might blame youthful maximalism, but I knew him. Ettyn was entirely different. He was a good hunter and a thoughtful young man, except in cases that dealt with such legends. And if something caused him to act rashly, it was the weight of guilt imposed by primitive tales.”

Borisov had come to Kytoorken to write about the beauty of indigenous fishing and its meaningfulness as compared to the soulless commercial slaughter by the whaler crews.

But the story hadn’t come together. The Ettyn boy hadn’t fit into the preconceived structure; his dead body had ruined the composition. The words had collapsed under this weight. It seemed: remove the boy, and everything would work, but Borisov knew that the essay must be honest. He couldn’t excise the boy and hope the essay would survive such a surgery. Ettyn himself had told him about the whale people, and in those stories a human was something like a whale’s soul, its intelligent part, which could take physical form and leave the whale body at will—but not for long.

Without its “inner human” the whale lost its cognizance and became a mindless mass of muscle.

He couldn’t remove the boy from the story about the Chukotka whale fishing: the essay would become lifeless and wild.

“Perhaps the boy was born on R’evava?” the Polish man suddenly asked, clearly enunciating each word. These seemed to be the first words he’d uttered since they all introduced themselves. “Is that why you came to this island?”

Borisov said nothing. Then Krzysztof added, “I also have a story about a whale.”

Krzysztof: Memories of the Ethnographer

Krzysztof didn’t really understand why he’d interjected himself into this conversation. Words had been Jacek’s domain. Krzysztof didn’t like words, which is why he put so much effort into overcoming them. But, even having added two more languages to his native Polish, he was no match for Jacek.

“You seem to think that faith in such things is the lot of naïve people unspoiled by civilization. My brother had two PhDs; he traveled across half the world and wrote several books. Jacek Tominski. Perhaps you’ve read his Whale Songs. He believed that at least one white whale—such as is described by the residents of R’evava—exists.”

The caretaker nodded. “He was a great man. No one listened to stories better than him.”

Krzysztof looked at Umilyk in surprise. He understood better and better why his brother had come to love these people. It was like leaving a smog-filled, dusty city, a dodgy society obsessed with mutual profit, compromises, and things left unspoken, and heading out to the simple and clear edge of the world.

Umilyk had noted the most important detail: no one listened to stories better than Jacek. It had always been so. There was a storytelling talent, and there was a talent as a listener. The way Jacek listened, he could turn anyone into a talented storyteller. Jacek could suss out a true melody in the white noise of anyone’s most awkward narrative. He could see it, touch it, clear it up, and admire it.

When he’d lacked words as a child, Krzysztof had played the piano. His fingers caressed the keys. Jacek had listened, and then told the story, and Krzysztof was amazed at how his brother had fished the words out from the current of the melody, like fish from the river.

“Jacek and I hadn’t seen each other in many years. He wrote me letters regularly. I replied inconsistently and grudgingly, but even in my abbreviated style my brother managed to glean everything important. He wasn’t counting on my own insight, so he described everything willingly and in great detail. That, and not my sensitivity or attention to my brother’s hobbies, is the reason I know quite a bit about R’evava and the white whales. You see, people here believe that anyone who was born on the island and lived a worthy life won’t die, won’t become a pile of ash in a Soviet crematorium or a stack of rotting bones in Soviet ground; won’t remain a portrait of an exemplary production worker on a factory wall or a few lines in the local or even a Moscow newspaper. No, they believe that white whales will come for the good people. It seems it always remained a mystery to me whether my brother was a good person. He never finished writing his last letter. This is all that I have left of him.”

Krzysztof took the small mouth harp from his pocket, which Jacek had sent him a few years ago. Seemingly Jacek had nothing like that in mind, but Krzysztof considered it a matter of honor to learn this language, also. Too bad his brother would never hear him play.

“You came to pick up your brother’s body?” the young woman asked quietly. Only now did Krzysztof realize she’d been carefully following their conversation, and even participating in it with her silence.

“The Chukchi people have this capacious word: enan-otkynatyk. It means ‘to carry the decedent on a sleigh while sitting astride them.’ I don’t think these wonderful people imply something greater here—some sort of metaphysical depths. But I see those. I think it’s about the importance of letting our dead go, instead of dragging them along as a weight. I came here to let my brother go. There’s no body left, and maybe that’s for the best. First, I won’t have to ride astride him on a sleigh. Second, I absolutely do not want to see him dead. People change too much in death. It’s not surprising that death gives birth to most of the myths.”

“Do you have two university degrees, too? You speak very well.”

“Not at all; I’m just a musician. A humble pianist. And a bit of a parrot. My brother used to speak well and write me eloquent letters; I’m merely repeating after him. It seems to be my destiny to repeat others’ melodies and words. But I promised you a whale story. Here I will also act as a parrot: the story isn’t mine.

“You’ve read Moby Dick, of course? A great book. My brother loved it very much. And, of course, he had a theory. Jacek had a theory about everything. When they say a person is looking for patterns everywhere, they’re talking about my brother.

“The Chukchi have the concept of teryky, a shapeshifter. This is usually used to describe a person taken by the tundra. Such a person becomes wild and loses themselves.

“Imagine a whale person who’s lost their human component. Won’t they become a teryky? And if so, will people call them Moby Dick?”

“Would that make your brother Ahab?”

Krzysztof thought it over, his chin down to his chest.

“Perhaps not. I’d say, Ahab’s opposite. Do you know why the boy who killed the white whale lost his mind from grief? It’s not because he killed a brother. That is a knowable human motive which people practice on a daily basis. But, as our loved ones lose their substance and form as they leave us and it becomes replaced with idealized features, so do our legends with time become gods. You see, people desperately need gods. This is, as your expression goes, fundamental to their moral compass. A god is not necessarily an incorporeal bearded old man in the sky. It’s not necessarily a young man on a cross. Sometimes a god is a flesh-and-blood person whom you’ve designated as your judge. And sometimes, it’s an enormous white whale. That’s what happened to that boy. He killed his god.”

Krzysztof fiddled with his vargan for a time. His fingers felt the instrument coming to life, inspired either by the conversation or by the storm outside the window.

“My brother wasn’t concerned with gods. Jacek believed in white whales, but he wanted to meet them as an equal. Person to person.”

“To meet them how?”

“It seems there’s no method other than to wait. At least, that’s what my brother thought. Unfortunately, he ran out of time.”

Krzysztof quit resisting and let the vargan take over. When he clenched it with his teeth the sound seemed to be born on its own, even before his fingers touched the reed. Focused on the emerging melody he didn’t immediately notice that the old woman had joined the conversation.

The old woman spoke quietly and Krzysztof couldn’t make out the words. After a moment he realized that even if he could hear her, he wouldn’t have understood: the old woman was speaking the Chukchi language.

Umilyk began to translate quickly and without hesitation, as though he’d been waiting for her to speak.

“Navetyn says that she has a story about a whale,” he said.

The old woman’s voice sounded like she’d picked up the vargan melody, chewed it with her toothless mouth, and then weaved it into a narrative thread. Krzysztof closed his eyes and suddenly felt what he thought his brother had felt. The voice lulled, even more noticeably due to Krzysztof not understanding the words. And yet he did seem to understand them, their meaning and spirit, their melody; seemed to dive into that river and then the current took him away before the caretaker spoke, translating the old woman’s words into Russian.

Navetyn: The Legend of the Woman Loved by a Whale

There lived a woman in the village of Nunak who had no husband. On rare occasions such women become huntresses, and they say there are no better huntresses than these. The bearded seal does not like the smell of a man, but he lets women approach closer. This is because a long time ago the seal tribe was equal to the humans, and the seal people took human wives. They still remember this.

The woman from Nunak was no huntress. Her pekul was rusty and the kerker and kamleika clothing she sewed were only fit for a shapeshifting bear.

But the woman knew many strange songs, and she taught these songs to others. There was a special song to make it snow, and another to make it stop. A song for a calm night, and a song to summon a pusa seal.

When hunters would return with a bearded seal, harbor seal, or a whale, the woman would take her rusty pekul and come for her share; no one dared to say anything to her.

The woman lived alone; she walked along the shore in solitude, and she sang.

The songs the woman sang were passed on to her by her grandmother, but the purpose for some was not known. At times the purpose was clear from the components of the melody: the woman recognized in her song the elements of snow and night and silence, and knew that this song was for a restful winter slumber, such that it would allow one to wake up full of energy and joy.

One song she could not understand. It weaved together the blizzard and whale calls, but the woman could not make sense of this combination.

One evening, at the edge of dusk, during the days of November blizzard, the woman stood on a rock and sang. She saw all the signs of the oncoming storm, but she didn’t rush home. She decided to see whether the song would work if sung during the blizzard.

And then it was too late: the blizzard crashed upon the earth and the world disappeared. The song dissipated in the howl of the wind, and the woman realized she could not find her way home.

Then the stranger came. He said: I will guide you. He took her by the hand and led her through the storm, and when the gusts of wind were especially strong he stopped and hugged the woman tightly, shielding her with his body. And the wind had no power over him.

He led her home, and he stayed the night, then left in the morning.

Ever since then the man had come almost every night, until the woman was with child.

One time the woman had followed him all the way to the sea, and had seen the body of an enormous white whale towering over the shore. When the man approached him, the whale had opened his mouth and the man had walked inside.

That’s how the woman had found out that she’d become the wife of a whale person.

This didn’t change anything in their lives: the woman sang her songs, and the man came when she called. Sometimes he stayed the night, sometimes two. But never more than three. He said that he could not leave his whale body for too long. Without a soul the whale would grow bored, become unpredictable and violent, lose his mind.

But it so happened that the woman fell ill. Neither the shaman potions nor the seal fat would help. Nothing could warm her. The woman lay in the middle of the well-heated living area of the yaranga, wrapped in bear furs, and it seemed she would be covered in a layer of ice at any moment. The people of Nunak did not know the reasons for her illness and therefore could not help. But the reason was that the child in her belly was a snow whale and he needed special songs to grow peacefully and not to accidentally kill his mother.

The whale-father stayed with his human wife and sang to her these songs. While he was near, the whale cub in her belly calmed down and the woman became warm and comfortable. A day went by, then another, then a third, and a tenth. Finally the danger had passed and the woman regained consciousness. She stepped out of the yaranga to get meat for dinner from the icebox, and she saw the people of Nunak celebrating and sharpening their knives. The news came that the hunters had harpooned an enormous white whale, which brought joy to the entire village. The woman rushed back to the yaranga, but it was too late. Her husband was no longer there; a small pile of snow was all that remained of him.

The old woman stopped talking, and so did Umilyk.

Umilyk knew that his retelling was akin to carrying snow in a sieve through a hot yaranga. Awkward and impractical, but when there’s no choice it’s better to bring however much would make it through.

A transparent and thoughtful silence hung in the room. Only then did Umilyk realize that the blizzard outside had stopped.

“What happened to her?”

It was the woman with dead eyes who spoke. Umilyk had seen her follow Navetyn’s tale with great interest, but didn’t think she’d dare to ask a question. And when the old woman replied, he was surprised even more. Although the old woman’s tone was grouchy, Umilyk thought that if her words were given form, they would emanate warmth.

Umilyk translated: “This is a simple story, as comrade Borisov says. The woman who carries a snow whale within her, becomes a part of the whale tribe herself. Of course, the mother of white whales came for her.”

“And the people of Nanuk simply let her go?” Borisov asked skeptically. “This woman knew many important songs. Surely they understood the benefits of her presence.”

The old woman spoke a short phrase and Umilyk hesitated for a moment, seeking the right words. For some reason he thought it important that the translation should sound equally poetic.

“Everything in this world has its own song: the people of Nunak forgot about the woman as soon as the snow powdered the traces of her footsteps.”

Borisov laughed and turned to Olga. “Well then, it’s your turn. Do you have a story about a whale?”

Olga: A Story about a Whale

“Do you have a story about a whale?” the Muscovite had asked, and his smarmy tone had made her shrink. It was like a scalpel cutting skin, to see what was inside.

The boy in her belly shifted. She somehow knew with certainty that it was a boy. Maybe because Aiwe had said so, and he always spoke the truth.

This child knew everything about her, and, it seemed, he really wanted to live. She felt him kick any time her thoughts strayed in the wrong direction. In those moments it seemed the darkness she’d fallen into after Aiwe’s death didn’t quite recede, but rather gained dimensions and depth.

No one is to blame, the doctor had said. Aiwe’s heart stopped first, and a few seconds later the beam fell from his weakened hand and crushed the big, strong, handsome Aiwe.

The doctor was short and skinny and very young, and Olga could see herself from three years ago in his gray eyes. She was like that during her early days in this monochrome world that seemed so flat, demonstrative, unreal—like a hastily erected prop for a movie about life in the far north.

But when it came to his area of expertise, the doctor transformed; his voice gained confidence, and his mannerisms became harsh. Olga noted in passing how she would enjoy watching a professional metamorphosis like that under different circumstances. But now, it was as though the automated registrar of what was happening wouldn’t turn off, and she watched from the sidelines, wrapped in darkness and grief.

Grief can have different tastes. Olga’s grief had an aftertaste of whale fat: the day Aiwe had died, a whaler brigade from Kytoorken had returned from a bountiful hunt. It was a major event and a holiday for the entire village.

Of course she’d heard about the boy from the Muscovite’s story. So very young, he’d tried to scare off a bear and her cubs alone. A tragic death. Except Olga hadn’t known he was a whaler and that the Kytoorken whale prize was, in part, his accomplishment.

After Aiwe had died, reality became something like an avant-garde black-and-white film, some weird French production with experiments by the director and cameraman. Olga kept losing the narrative thread and finding herself in the center of various events. Here was Aiwe’s death certificate, and arguments with officials who didn’t know where to record the man who was not written into any of their thick books; here she was in the school director’s tiny office—indifferent but inexorable, she had no strength to remain in Kytoorken; here she was at the post office, making a long-distance call to Tashlinsk, her mother’s accusatory tone when she found out about the pregnancy; here was Umilyk serving her tea, and Borisov with his story, and Krzysztof, and the old Chukchi woman.

Somewhere in between all that were the nausea, melancholy, nightmares, and the endless kicks in the stomach. She had no time for the young hunter, whose death, it turned out, was tacked on with a red thread to her own life. Olga imagined how in some other small Chukotka village someone was drinking tea and mentioning her Aiwe’s death in passing, as an afterthought. This always happened with the dead: they left behind only brief threads of conversation, someone’s unreliable memories and, with any luck, photographs. What sort of cadaver could be put together from such materials? The boy from the Muscovite’s story appeared wholly alive. Olga could easily imagine him, and could seemingly even hear his voice in the song of the blizzard. Could she so deftly create a verbal portrait of Aiwe for their son?

“Do you have a story about a whale?”

Aiwe had brought her to the shore and they’d watched the whale. Olga hadn’t known how to see it at all, but Aiwe had showed her where to look and how to see. He’d told her to listen to the whale song. Olga had listened in earnest, and he’d hugged her and told her that she must listen not with her ears, but with her heart.

Now Olga thought she had no heart left. Above the spot where her boy’s tiny heart beat there was a cold emptiness.

Aiwe had appeared out of nowhere; one day he’d walked into her night school and said, “I heard your voice and came to see.” Since then he’d come every evening, hadn’t asked for anything, hadn’t courted her, and hadn’t flirted. Olga didn’t even understand how it came to be that he’d become the most important person in her life.

How did it come to be that, by leaving, Aiwe had taken her life with him? Olga felt herself a shadow that had no place in any of the usual worlds.

She realized that she couldn’t remain in Kytoorken, but her native Tashlinsk seemed alien and flat. Olga felt stuck between two worlds, the higher and the lower, and rejected by both. Sometimes she overcame the feeling of utter foolishness and asked the boy in her belly: where to?

“Do you have a story about a whale?”

Sometimes she listened the way Aiwe had taught her. Not with her ears, but with her heart, even if only its tatters remained. And when she listened like that, she thought she could hear her boy. He sang the way the whales sing.

The old Chukchi woman, Navetyn, was now singing, too. Her whispers intertwined with the moans of the vargan, mixed together, tamed it. Everything disappeared: the people, the weather station, the waiting, the questions. Only the blizzard and the voice of the great mother of white whales remained, and it called to her: come with me.

R’evava, the Whale-Island

Umilyk stepped out onto the porch to catch a glimpse of the snow whale’s tail as it swam away into the darkness.

The silence after a blizzard is a special time, and a state of mind. As if the entire world stops and freezes. And it listens: what now? Did it survive? Is it whole? Are the north and south poles still in their place?

The silence after a blizzard is so piercing that it seems possible to hear the thoughts and aspirations of all nearby creatures. This silence binds them all together into a single net. Umilyk listened to the stars; they rejoiced at the return of the snow whale. He listened to the sea calming under fast ice; he could seemingly even hear the helicopter preparing for flight in the distant town of Pevek.

Umilyk heard Borisov’s thoughts. Borisov, who stepped onto the porch after him, was sad in the way a hunter is sad after an unsuccessful hunt.

Krzysztof stepped outside and from his gait and the movement of the air, Umilyk realized that the musician was fascinated by the beauty around him. Krzysztof had already put away the vargan, but the melody still sounded in his thoughts.

Umilyk wondered whether he should tell the Polish man that he’d seen his brother talk to the sea on the final day of his life. Had seen him board a whaleboat on his way to meet a whale. Had seen the storm being born on the horizon. If he should say that he still wasn’t certain whether he should have stopped him.

Instead, he said: “You know, this was the first time in thirty years that I witnessed such a long telling by the old Navetyn. What a story, huh?”

“Navetyn?” Borisov asked absentmindedly. It was clear that his thoughts were already in Pevek, in Magadan, in Moscow.

Umilyk glanced at Krzysztof, who only raised his eyebrows in solidarity with Borisov’s question.

“The helicopter is almost here,” said Umilyk, to change the subject. The image of Navetyn in his mind grew dim and out of focus, as it happens when you don’t see someone you know for a long time.

“Listen,” the Muscovite voiced a concern. “I was told another passenger would be joining us, a teacher from Kytoorken. We aren’t going to wait for her, since she couldn’t be bothered to arrive on time, are we?”

Umilyk shook his head. For another moment he listened to the sound of receding footsteps—the almost inaudible steps of an old woman and a young one. And then he stared at the gloomy sky, catching a few stray snowflakes with his face—the final greeting from the snow whale.

“Songs of the Snow Whale” copyright © 2024 by K.A. Teryna; translated by Alex Shvartsman

Art copyright © 2024 by Marie-Alice Harel

Buy the Book

Songs of the Snow Whale